10 Years On: Blackstar Signals Arrival As Much as Departure

“The truth is, of course, that there is no journey. We are arriving and departing all at the same time” - David Bowie

If an artist is both endowed with a zest for the philosophical and an undeniable ability to translate spiritual yearning into music with clarity and immediacy, an impassioned audience will flock to them as a kind of meaning-maker or prophet. Tenth, twenty-fifth, and fiftieth anniversaries in particular tend to invite fond remembrance, and audiences - especially those in a permanent state of grief over a beloved artist’s death - want an anniversary piece to feel simultaneously conclusive and inspiring. So, then, what does one do with an artist who spent his career committed to undoing coherence and entirely allergic to confessional readings?

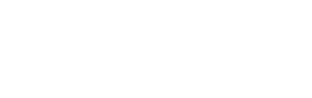

David Bowie’s cryptic, avant-garde, persona-warping Blackstar reached its 10th anniversary on January 8th. Written and recorded during a gruelling 18-month struggle with cancer - kept entirely out of the public eye - the record emerged from a surge of creative re-energisation following Bowie’s late-career ensconcement in New York’s avant-garde jazz scene. After collaborating with Grammy-winning composer Maria Schneider on Sue (In a Season of Crime) Bowie also reengaged longtime collaborator Tony Visconti, whose ear for experimentation and knack for translating emerging synth technologies into rock had helped propel the Berlin Trilogy decades earlier; even James Murphy of LCD Soundsystem briefly contributed percussion before bowing out under the weight of the project’s significance. It was Bowie’s terminal diagnosis, however, that forced the album into focus open-ended experimentation into a race against a conspicuous clock, forcing Blackstar into focus as an urgent study of the liminal space between diagnosis and death. He released the record on January 8, 2016 - the day of his 69th birthday - and was announced dead two days later to a cacophony of critical and audience speculation.

The story of Lazarus appears in the New Testament’s Gospel of John and Secret Gospel of Mark, an extended but fragmentary account in which Jesus raises Lazarus of Bethany from the dead four days after his entombment: typically, the impetus of the narrative is an affirmation of the religious capacity for the continuation of life on a cellular level while simultaneously projecting the death of the ego onto the far more consequential planes of spiritual purification. Bowie’s single ‘Lazarus,’ written post-terminal diagnosis, released in December of 2015, opens with “Look up here/I’m in heaven” - a semantically promising sentiment that grows increasingly less convincing as Bowie’s booming yet clinically acidic voice replays grandiose worldly pleasures brushing against implied retroactive realisations of spiritual vacancy. Visually, the Lazarus video holds as much weight as the song. Bowie is depicted blindfolded, button-eyed, rising from the bed, sporting anything but Christlike radiance: he’s restrained, wielding humour without warmth, and gaunt and pale enough to be safely assumed an artistic statement. Setting an immediate standard for the record of resistance to narrative flattening, it layers multiple timelines as its chambered, dry monotony grounds woozy ascension, encapsulating the thudding claustrophobia of pre-death reflection and the lightheaded ascension towards endless post-mortem possibilities. This reworking of the Lazarus myth frames salvation not as fulfilled - nor as pure mortal death in the preconceived sense - but as resurrection stripped of hit-and-run clarity. It is representative of something far more disturbingly cyclical and carnal than resurrection fulfilled or punctuative death: ‘Lazarus’ is the flippant testimony of a man in flux of cosmic experience who has found purgatory without a clean path forward or meaning in continued time.

Opening title track ‘Blackstar’ - stylised as ★ - embraces symbolic friction and rebellion as shamelessly as ‘Lazarus,’ dropping into immediate critical speculation and - whistleblowers working as vigilantly as we’d all hope - was seized upon by Satanic Panic corners of the internet as evidence of hell’s unflinching grip on the music industry. The ten-minute centerpiece moves like an occult liturgy despite maintaining roots in Bowie’s synth-driven glam rock, combining propulsion with restraint and elegance to sweep listeners straight into the vaporous yet unflinching energetic center of the record. ★ represents Bowie’s coolest and most disciplined form of philosophical and religious introspection yet: laden with ritualistic imagery, biblical allusion, and ceremonial viscosity. Blindfolded women encircle a fallen star; a solitary candle burns; Major Tom’s jewelled skull is ritualised as it elevates - visions punctuated by the thudding reassertion, “I’m a Blackstar,” and religious provocations like “You’re a flash in the pan / I’m the great I am.” In declaring himself a “Blackstar,” Bowie positions himself simultaneously as luminous and isolated; central, yet untouchable. The title functions as both cipher and declaration. He becomes the cosmic focal point around which meaning appears to orbit, while refusing to resolve, soften, or explain that center for the audience. In this sense, the Blackstar is both a literal and symbolic apex - a devouring touchpoint of ritual, and ultimate nebulous brilliance.

This prioritisation of artistic gravity over guided catharsis is mirrored in the song’s architecture. Its rhythms fluctuate yet never resolve; its motifs circle and amplify rather than evolve; its shifts feel less like development than reincarnation with sonic ideas returning altered, degraded, or eerily familiar, but never quite sticking the landing. Meanwhile, beloved persona Major Tom in Space Oddity grows tired of the tedium and predictability of life on Earth, taking to the stars to get his fix of cosmic wonder. Over time, that fantasy curdled. By Ashes to Ashes, Major Tom had returned not enlightened but strung out, recast as a junkie haunted by the very escape he once reached for (likely allegory for his cocaine-ridden L.A. days). Blackstar completes the arc with chilling finality. No longer drifting, narrating, or seeking escape, he is reduced to an artifact: Bowie’s long-held fantasy of transcendence through escape is rendered inert, vacant, and ultimately bone-dry.

The ghoulishness of the tracks almost makes one forget what a far cry the record is from the existential gratitude and wonder of earlier-career tracks like Starman, the classically lilted track centered around the idea that there is some sort of cosmic significance waiting to imbue our lives with automated meaning. And, of course, we’re all familiar with alien persona Ziggy Stardust: he was cursed with screwed-up eyes and a snow-white tan, but made up for his shortcomings with his God-given ass and prowess on the guitar. His deployment of characters like Major Tom and Ziggy Stardust granted him enough anonymity to explore subversive topics in the lane of sexuality and religious agnosticism met with mysticism (about as concerning a combination as possible in more traditional circles). The inflection point in an artist’s career - when every next move is guaranteed coverage, yet audience expectations haven’t fully hardened - reveals a great deal about their creative archetype and what they seek from the industry. By inventing - no, unearthing - Ziggy, Bowie chose a move divisive enough that it established his mutual desire for rock fandom and audience admiration, yet incisive into the most delicate veins of cultural expectations that hitting the wrong nerve could cause him to lose the type of audience to be bound up over the gender of shoes. Bowie spent his career in the spotlight, either being accused of cuteness by pejorative skeptics or an audience excavating his work answers he never claimed to possess.

As it’s said, all press is good press: Ziggy Stardust scratched a festering itch in the alternative discourse and hard-fought progressive movements of the early 70s, causing the enigma to reach a fever pitch of fandom paralleled to the beginnings of Beatlemania. “I became Ziggy Stardust. David Bowie went totally out the window,” Bowie shared in a 1976 interview with Rolling Stone. The struggle of separating the art from the artist is often discussed in creative circles, but Bowie struggled with the inverse: the inability to separate the art from himself. Ziggy Stardust embodied both escape from himself and a crisis of identity - the liberty of shedding artistic hangups while carrying the full weight of myth, a logic that Bowie spent the rest of his career attempting to outclass.

Steamrolling out of the emotional catharsis of Blackstar’s first - and only - explicit acknowledgment of Bowie’s impending death on the incendiary ‘Dollar Days,’ ‘I Can’t Give Everything Away’ confronts the weight of legacy with tortured peril. “I know something is very wrong / The post returns for prodigal songs,” Bowie admits with a growing wobble in his voice, signalling his awareness of the audience’s expectation for a final gesture of artistic generosity: instead, he offers refusal as the title line becomes less convincing as a hook than as the sound of a body emptying itself of its last steady air and semblance of composure. As with the rest of the record, the song privileges absurdist continuation in its answerless motion, jazz riff-offs that refuse calcification, and energy that mists rather than detonates. The fitting - and acceptable - choice for an unexterminable icon would have been a retrospective victory lap, collapsing Bowie’s many life-forms into a single nostalgic summation. Instead, he opts for subtraction - a methodical stripping-down toward his least performatively consoling essence - bowing out entirely before further disclosure would detract from his dignified exit more than it would add to the creative capital of the project.

Blackstar is often metabolised as “the Bowie album that stands at the crossroads of death and legacy”, but that analysis feels far too diminishing: while Bowie may have lost himself many times over to his fragmented approach to identity, death, and rebirth, the very perception of death through his philosophical lens opens death to be less of a final stop, and more generously interpreted as another phase in an endless process of collision, regeneration, and reconfiguration. To frame the album as an emblem of dignified farewell is to misunderstand Bowie’s lifelong philosophy that every part of life - meaning, forward movement, belief, engagement, and even coherence - is a choice. Death is not. Within this framework, the parting statement is not a nihilistic march towards, but a reminder that potential finality doesn’t lend immediate translucence to the unresolved ambiguities of life.

The album may soundtrack Bowie bracing for departure from his body, but it also signals a quieter arrival. In his final work, he reaches the internal destination his career spent decades circling: the confidence to remain off-kilter, cryptic, and resolutely answerless without offering comfort. He is killing his stars while simultaneously morphing into one; dying while living on; resurrecting while rotting; stripping himself raw for the world to criticise without giving anything away at all. Amid the negative space, resistance to closure, and existential vertigo, Blackstar offers a rare glimmer by fully inhabiting the truth Bowie spent a lifetime approaching and articulating: “The truth is, of course, that there is no journey. We are arriving and departing all at the same time.”

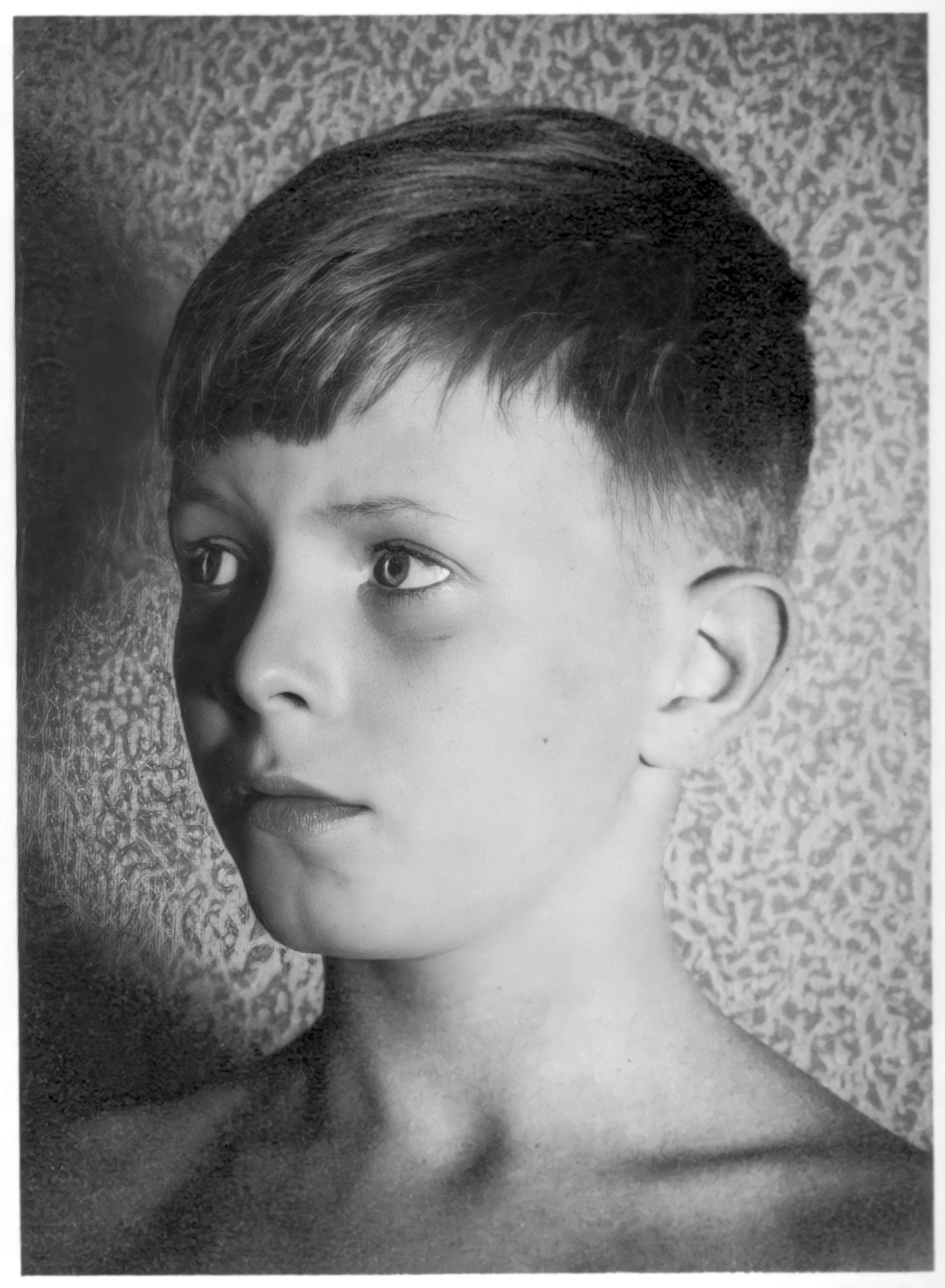

PHOTOGRAPHY: Young David Jones at Plaistow Grove - Credit David Bowie Estate