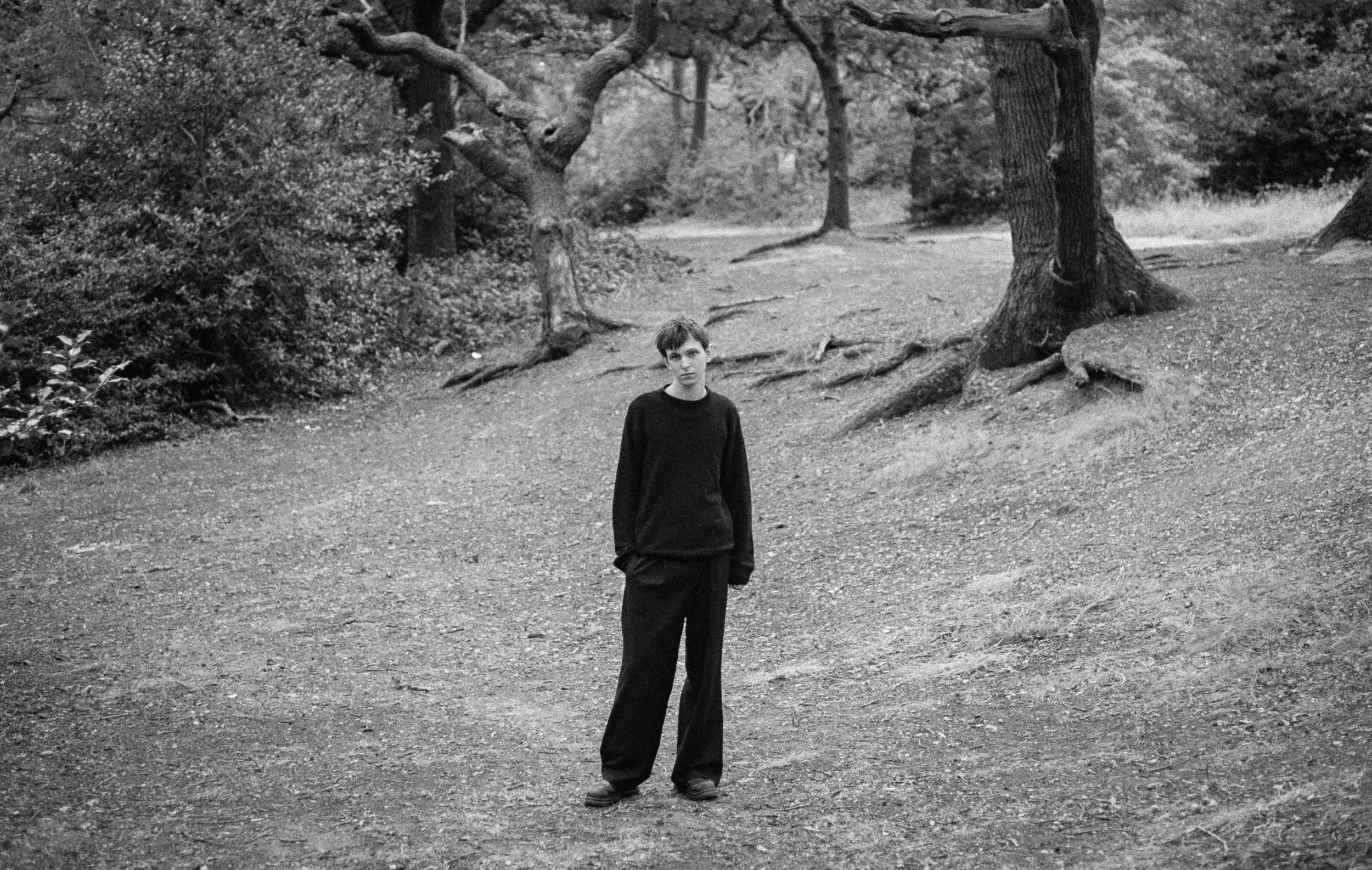

Start Listening To: Henry Coke

An artist searching the edges of belief, using choral language to question the silence it comes from.

Henry Coke writes music that feels like a dialogue with the divine, even when the only voice you hear is his own. Raised in a family of vicars and shaped by years spent inside choirs and cathedral spaces, he carries the weight of that lineage into a project that both honours and unsettles it. His songs sit at the intersection of faith and frustration, where sacred harmonies collide with doubt, anger and an almost visceral longing to understand why belief slips away. With ‘Out Of Time’, Coke opens that tension fully, turning a private confrontation into something stark, emotional and strangely beautiful. In this conversation, he reflects on the traditions he inherited, the myths he’s dismantling, the writers and filmmakers who sharpen his darkness, and the sound of trying to speak to something that may never answer back.

For those unfamiliar with your music, can you tell us who you are, where you’re from and about the music you make?

I’m Henry Coke, I’m an artist and producer from London. I write alternative music that has choral and spiritual influence. It gets quiet at points, and loud and screamy at others.

‘Out Of Time’ feels like a confrontation, almost a reckoning. When you first wrote it, did it arrive as a deliberate conversation with God, or did it spill out before you even understood what you were saying?

I wrote an entirely different song to the music I recorded initially, and I hated it so I rewrote the song as a confrontational conversation. ‘Out Of Time’ really started it all for me for going down the route of religion and questioning in my music. At least this explicitly. I decided to write my lyrics as one big verse, which is how I view the structure of this song. And as I kept developing the scene I was writing about, it came pretty clear to me what I was writing about. A lot of my songs are born out of one of the first lines of the songs, which is usually a subconscious sign of what I want to write about. I always stop and try and decode these random phrases that initially come with the music. It felt like a big risk writing this conversation in this way. I think it’s important that we only hear my side of the conversation in the song. I don’t think there will be a kind of reply, at least not in word form if there was to be anything.

You come from a lineage of vicars and church leaders. How does that inherited weight sit with you now, especially as someone who’s moved away from the church but still carries its musical language?

I think I find myself aware of the listener more because of it. Learning to play music in the church teaches you about singing in front of a group of people as a non performative thing. Singing and playing in church isn’t for people to listen to you, it’s for a higher power and for themselves to reflect on the words that they are also singing. I want an element of that to my music, I want to be able to also be on the listeners side, a congregational connection. When I sing about myself, I struggle with the selfishness in that - but being aware of that and struggling with the comfort in doing so, is something that I carry from my family. They’ve all given their life to lead people in a faith and I’ve just gone and written songs about how I feel.

Your backing vocals echo choral arrangements and cathedral acoustics. What is it about sacred harmony that still feels essential to how you write, even as you push against the belief systems you grew up with?

It’s how I learnt to sing harmonies! I went to different choirs from when I was little and just continued to do so… until I learned to record myself and I just became my own choir. The choral world really influences every kind of harmony and chord I write, when there’s a piece of long drawn out clashing chords of voices I think it’s the most beautiful sound. And there’s a version of that for every corner of the world which is so inspiring. I love that most of choral music isn’t in English and I can’t understand the words that are being sung right away. I have to go out of my way to find the translation of what’s being said, leaving the harmony to be the first thing to listen to. I think that the fact that I use those choral arrangements and cathedral acoustics in the backing vocals is an oxymoron to what I’m singing about, it’s kind of this lurking feeling that will always be there.

The line between rage, grief and longing runs right through ‘Out Of Time’. How do you navigate writing about faith when the emotions are often contradictory or even antagonistic?

I’m still trying to figure it out. I think the idea of God, and how people view it, is different for each person. My God - I don’t know if I have one, I think some days I do - is what I see in the people and feelings that I love, in kindness and graciousness; the questioning itself rather than the answers and coming to terms with that; the feeling of making music, that flow state of trying to figure something out and the realisation that hours have passed. I’m aware of the religious people who will listen to my music and see a Christian God in the words and assume that, and I’m okay with that, that’s the language I’m speaking and what I’ve come from. I like people making their own interpretations. And I like contradicting faith and hope with non-religious things in the same lines too, I think I’ve pissed off quite a few, more conservative, traditional Christians by swearing and dropping the F bomb at God. Which is great, I love that.

You talk about hearing silence, about directing words at the divine and finding only a void. How do you translate that spiritual absence into sound?

I don’t. The music is pretty packed out with different parts of the music, I think of those as constant running thoughts instead of the spiritual absence and silence. When there’s moments of absolute nothingness, like the part before the final section of ‘Out Of Time’. It’s the “Faithless dying moment” of silence - leaving space for an answer but not much time to do so. I think there’s a nagging feeling that sits in the back of the music, maybe a part of those backing vocals, the spiritual connection to my past and upbringing. The silence should be loud.

Forcing the live band through a four-track cassette machine is such a striking choice. What does that physical limitation allow you to express that clean digital sound can’t?

It’s mainly the unpredictability of it, the four track can end up sounding different every time, the knobs aren’t exactly the same even if you put everything to the same settings every show. They can get knocked as you set up and completely change the sound. I love the dynamics that come with my guitar running through it, there’s this sweet spot where I have to play ridiculously soft to keep my guitar clean and then dig in a little bit to get it to break up and distort. There’s a song we play live called “Regret (You Make Me)” where the bass synth is super loud and prominent. It goes through the four-track at the same time as my guitar and the two elements uncontrollably fight for the space in the music, that’s what I love about the four-track. Everyone has to be aware of the space, to play with caution in the dynamics, in a breaking up distortion sense, rather than volume and play style. And with that unpredictability, the role of who is in control of that, changes set by set.

Your influences outside music — Rilke, Flannery O’Connor, David Lynch, Philip Ridley — all deal with mystery, dread, transcendence. Which of those storytellers shaped your lyrical voice most directly?

Probably Rilke, I like to read poem books and take random words that pop out to me and start lines that influence whole verses of songs. I love how he leans toward the darkness in faith - dark corners to pray in, or the darkness in fearing God. Which is similar to Flannery O’Connor, her strange Southern Gothic reflections on faith really help with finding non biblical imagery of questioning a God. Philip Ridley is a funny influence to me - he wrote a few children’s books, which I loved as a kid and would dress up as the characters. His stories have a surreal darkness that aren’t usually in children’s books, strange characters that make no sense and settings in abandoned places. He then made this coming-of-age horror film “The Reflecting Skin” set in a small town in America, a work of his that has influenced me more recently… in fact I forgot about him until I found the movie. It has this endlessness to it, endless fields of wheat and emptiness and endless meanings to things that just spontaneously happen in the film. I think I aim for that endlessness in some of my songs, like the never-ending questions of divinity.

‘Out Of Time’ touches on the fear of being too late, of missing the chance to believe. Is that a personal feeling or something you see reflected in the wider cultural moment too?

Yeah a chance to believe is a personal feeling I guess, feeling the belief slip away. Going to a point of no return, and drifting so far away from faith, that I’d never get to that point or kind of faith again. But I guess there’s an element of the wider cultural moment too. There’s a lot to be hopeless about, the rise of AI, the far right, tyranny, the planet dying - it doesn’t give you much hope for the future and these are all elements of going past a point of no return, it’s too late to fix these things now and we just have to live with the consequences whether we like it or not.

What do you love right now?

Falafel Wraps, 90s Slowcore, using pencil instead of pen for notes, reading comment sections.

What do you hate right now?

Spotify Wrapped.

Name an album you’re still listening to from when you were younger and why it’s still important to you?

Probably Bob Dylan’s ‘Time Out of Mind’. I remember seeing the CDs and records of that album in the living room as my dad was listening to it when I was a kid. He’s a huge Bob Dylan fan. It’s not Bob’s most successful or famous album but it really resonates with me and is by far my favourite. The production is really interesting, it doesn’t sound like any other Bob album, the guitars don’t sound like traditional acoustic guitars and he has this sense of time in that album. He doesn’t need to fit in a certain timeframe or want to get to the next section of the song, there’s a huge amount of space between each line he sings. Particularly the song ‘Not Dark Yet’ is a big one for me, he drones on these same few melody lines but it doesn’t feel repetitive, and if it does, it makes sense, he says “but it’s getting there” - the darkness, the end (of the song?) is getting there, we’ll make it to the end.

When someone hears your music for the first time, what do you hope sticks with them?

I hope the emotion is the first thing to be picked up on. I try really hard to make my music feel like it’s trying to get out of the constraints of a recording, beyond the audio file. To me, that feels and sounds emotional, and I hope that comes across.